What is Molar Hypomin?

"Molar Hypomin" is short for "Molar Hypomineralisation" (the technical term for Chalky Molars), a very troublesome D3 that causes lots of suffering and costs around the world. On the bright side however there is good reason to expect this widespread problem may eventually go away (i.e. become medically preventable), once scientists figure out what causes it – and that’s an exciting quest many families are helping us with.

Learn more about the basics of Molar Hypomin on this page, and then consult other pages in this FAMILIES section for straight-forward FAQs and guidance on how to get advice and treatment, take care at home, and support this under-nourished aspect of global health.

To learn about the worldwide impacts of Molar Hypomin, go to the COMMUNITY section for more detail on how common and burdensome it is, and then visit Social Impact to see how D3G's pioneering activities are making a world of difference.

For those of you interested in diving deeper, feel encouraged to see how we're reshaping the field to benefit prevention (D3G's 'MH Lifecourse Concept'), and perhaps also consult our bibliography of Molar Hypomin studies here.

What does the name mean?

As the name implies, a key feature of Molar Hypomin is that it’s quite selective for certain teeth. Molars of course are back teeth and those most prone to this type of D3 are the "6-year molars" – otherwise known as the first "adult" or "permanent" molars whose eruption into the mouth typically occurs at 6–7 years of age. Other molars can also be affected including the "2-year molars" in toddlers and the adult "12-year molars" (each about half as frequently as 6-year molars, see here). Sometimes in more-badly-affected children their adult front teeth (incisors) – which typically erupt during ages 6 to 8 years – can have this problem too. In this situation you may hear an older clinical term "Molar-Incisor Hypomineralisation" (or its abbreviation "MIH") used. While still popular in some areas, this old name has been superceded by "Molar Hypomin" (or "MH") for various reasons as explained here. "Hypomineralisation" is just a technical way of saying "abnormally low amounts of calcium mineral" – in other words, "Hypomin" describes tooth enamel that is often soft and porous (chalky) rather than hard and shiny white as normal. And it’s that

"chalkiness" which can cause problems, as we explain below.

What does it look like?

Molar Hypomin is easy to recognise when it also affects the front teeth – as seen in this bad case in a 10-year-old (top picture), the Hypomin enamel appears more opaque than normal and its colour may range from unnaturally "extra white" through creamy yellow to brown. The defective patches usually have quite obvious boundaries with normal enamel which is why dental people refer to them as "demarcated opacities". In contrast, opacities associated with excessive fluoride have a more diffuse appearance (i.e. dental fluorosis). This picture also shows how the problem affects some teeth but not others – whereas the two middle front teeth (central incisors) are really chalky, the next teeth outside them (lateral incisors) are both fine.

You can tell a lot about how bad the Molar Hypomin is just from its appearance. In mildly affected teeth, the defective enamel is usually "extra white" and the tooth surface is hard and intact (although perhaps a little duller than normal), as can be seen in the middle picture – those back teeth are the 1-year and 2-year molars in a 4-year-old. In moderate cases, the Hypomin enamel has more colour than normal (typically creamy-yellow) and the surface might have started to crumble (i.e. suffer "breakdown") as seen in the right front tooth in the top picture. In severe cases, such as the badly affected 6-year molar (lower picture), the chalky enamel is a creamy brown colour and so soft that a large "pothole" has formed even before the tooth has finished erupting. Note that these broken-down surfaces (potholes) often start out being simply the result of Molar Hypomin and have nothing to do with dental caries (i.e. "cavities"), as explained further below.

Dentists will grade the severity of your child's Molar Hypomin taking into account not only how badly each tooth is affected (i.e. colour, hardness and size of defective patch, plus any pothole development) but also the number of teeth affected and level of pain or sensitivity. The number of defective teeth can vary widely, from one to six or more. In mild cases, typically just one or two molars are defective whereas all four of the 6-year molars plus some incisors, and other teeth too, might be affected in particularly severe cases of Molar Hypomin. And what became of those chalky front teeth in our 10-year-old? We're pleased to say there was a happy ending! (click here to see the result)

What's the problem with it?

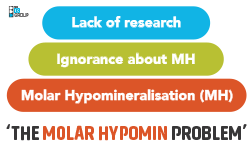

As with chalky teeth, we say "the Molar Hypomin problem" has three parts to it (original reference). First, there is Molar Hypomin itself which can trigger a variety of concerns as described below. Second, there is widespread ignorance about Molar Hypomin stemming from major gaps in education – these shortfalls extend across the healthcare professions and out to the public worldwide. Third, there is a lack of research-based understanding, leaving numerous unanswered questions about what causes Molar Hypomin and how best it can be managed or prevented. Read how The D3 Group is tackling all three

parts of this problem – under the broader umbrella of chalky teeth – here.

Unsurprisingly the chalky enamel in Molar Hypomin can lead to several problems – the three main issues for sufferers are sensitivity (dental pain or toothache), breakdown (crumbling & potholes) leading to increased risk of decay (from dental caries and/or acid erosion), and unsightly appearance in the case of front teeth. Dentists can also strike problems when trying to fix these defective teeth, and the medical system can be burdened by severe dental outcomes (e.g. emergency visits for advanced decay, general anaesthetics for multiple extractions). So, although Molar Hypomin kids can be perfectly healthy in all other regards, it's possible their dental condition can be quite troublesome and costly if not cared for well.

In Molar Hypomin the dental pain (sore tooth or jaw) might be triggered by hot or cold foods or toothbrushing, and vary in severity from a minor inconvenience to full-on disruption of daily life. It is important to realise that Hypomin teeth can be painful even if they show no evidence of potholes, cavities or dental caries. In other words, even children who have taken great care to keep their mouths free of decay (and fillings) can unfortunately end up with bad toothache as a consequence of Molar Hypomin. Not knowing this, some parents in the past have felt (quite inappropriately) that they were to blame for the "neglected" condition of these "rotten teeth". A good rule of thumb is, if the rest of the teeth are free of decay and it’s only the 6-year molars that are painful or crumbling, then there's a better than average chance that Molar Hypomin may be to blame (more on this here).

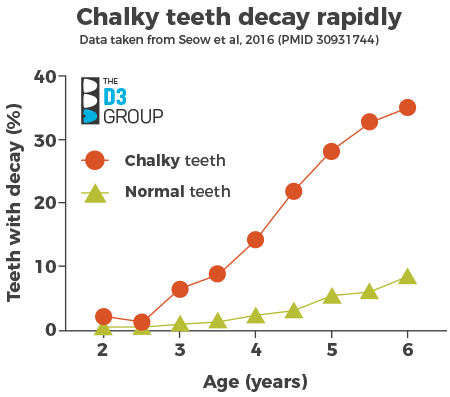

Putting pain issues aside however, those kids affected more severely by Molar Hypomin do have a higher risk of getting an unusually rapid type of decay for several reasons. First, when enamel is chalky and porous rather than shiny hard, the "plaque bugs" (bacteria) that cause dental caries can penetrate the weakened tooth more easily and so become inaccessible to cleansing with a toothbrush. This situation only gets worse when the enamel is really soft and crumbly, giving even more places for bacteria to hide and launch their acidic attack. Third, the extreme sensitivity of some Hypomin teeth can stop kids brushing in that part of the mouth, so aggravating the risk for decay – a dental example of a vicious circle. Reflecting these multiple risk factors, an Australian study found that, from age 3 years, decay was over five-times more prevalent in chalky teeth (mostly 2-year molars) than for normal baby teeth from the same mouths (see following graph). A major strength of this longitudinal study is that it followed the same group of children over several years, thereby avoiding many of the uncertainties associated with the common type of study that examines different groups of children at various ages (cross-sectional study). For more about decay risk go here.

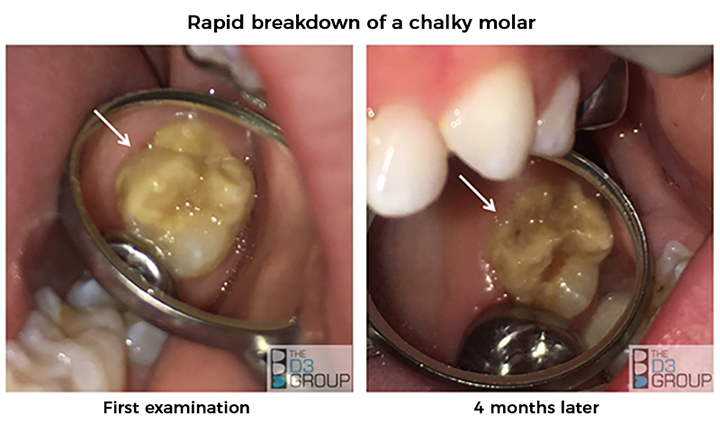

An overlapping issue is that chalky enamel might 'break down' (crumble) and form potholes simply due to the normal forces associated with chewing (mastication) – even before dental caries sets in. As shown in the following pictures of a chalky 6-year molar, such breakdown can happen in just a matter of weeks in severe cases of Molar Hypomin, putting the tooth at strong risk of a very short life.

Unsightly front teeth may not only lead to anxiety for the owner but also create awkwardness for onlookers. Fortunately, Dentists these days have many options for improving the cosmetic appearance of front teeth, and often these work well when the defective patches are relatively small. In badly affected molars however, the defective enamel can cause Dentists all manner of problems and as a result some types of fillings don't last as long as normal. Another problem is that sensitive Hypomin teeth can be slow to go numb with local anaesthetic, which of course is awkward for both Dentist and child. For these reasons, your Dentist might suggest using an alternative type of anaesthetic or refer you to a specialist (read more).