What Are Chalky Teeth?

Not surprisingly, being a colloquialism, "chalky teeth" means different things to different people. But what we can all agree on is that chalky teeth look different – most often the enamel has an abnormal colour, either being whiter than normal or having shades of cream, yellow or brown. This discolouration is usually restricted to a small spot or bigger patch, but the whole tooth surface may be affected in severer cases. Sometimes the enamel appears dull and opaque and also crumbles easily (i.e. "chalky", in contrast to the shiny hard surface and translucency of normal enamel). Other times the surface enamel is shiny but irregular, with pits or grooves being visible from some angles.

Not surprisingly, being a colloquialism, "chalky teeth" means different things to different people. But what we can all agree on is that chalky teeth look different – most often the enamel has an abnormal colour, either being whiter than normal or having shades of cream, yellow or brown. This discolouration is usually restricted to a small spot or bigger patch, but the whole tooth surface may be affected in severer cases. Sometimes the enamel appears dull and opaque and also crumbles easily (i.e. "chalky", in contrast to the shiny hard surface and translucency of normal enamel). Other times the surface enamel is shiny but irregular, with pits or grooves being visible from some angles.

The D3 Group has adopted "chalky teeth" as a public-friendly catch-all, meaning we're not at all fussy about  how the term is used. If you think one or more of your child's teeth looks a bit different and you're able to discuss this with a dental professional then that's great. Sometimes it might turn out that "chalky white spots" are actually the beginnings of tooth decay, rather than a problem with tooth development, and other times it might be a bit of both. You'll also know there are other reasons for teeth being discoloured, such as when a tooth has died after a knock. Leave it to a professional to sort out the details of what's what – but they can only do so if you make an appointment, and usually the sooner the better.

how the term is used. If you think one or more of your child's teeth looks a bit different and you're able to discuss this with a dental professional then that's great. Sometimes it might turn out that "chalky white spots" are actually the beginnings of tooth decay, rather than a problem with tooth development, and other times it might be a bit of both. You'll also know there are other reasons for teeth being discoloured, such as when a tooth has died after a knock. Leave it to a professional to sort out the details of what's what – but they can only do so if you make an appointment, and usually the sooner the better.

That all said, we think "chalky teeth" is a good term to use when beginning a conversation about teeth that haven't developed properly, leading to enamel that isn't as hard and resistant to decay as normal – and our second step in such conversations is to talk about D3s.

And for those who didn't arrive at this page from our Chalky Teeth Campaign, why don't you check out this world-first public-awareness initiative which seeks to convert medico-dental science into fewer

cavities in our children?

WHAT IS THE CHALKY TEETH PROBLEM?

We say "the chalky teeth problem" has three parts to it. First, there are the chalky teeth themselves which can trigger a variety of problems including toothache and accelerated tooth decay as noted above (more detail here) – these outcomes can be troublesome not only for people with chalky teeth but also for the dental professionals who deal with them. Second, there are major gaps in education about chalky teeth – these deficiencies extend across the healthcare professions and out to the public worldwide. Third, not much research has been done into chalky teeth, leaving numerous unanswered questions about what

We say "the chalky teeth problem" has three parts to it. First, there are the chalky teeth themselves which can trigger a variety of problems including toothache and accelerated tooth decay as noted above (more detail here) – these outcomes can be troublesome not only for people with chalky teeth but also for the dental professionals who deal with them. Second, there are major gaps in education about chalky teeth – these deficiencies extend across the healthcare professions and out to the public worldwide. Third, not much research has been done into chalky teeth, leaving numerous unanswered questions about what

causes them and how best they can be managed.

The D3 Group is tackling all three parts of this problem through this website and our other educational resources, and via the Chalky Teeth Campaign which advocates for research into the prevention of chalky teeth. Learn more about the chalky teeth problem and how we're fighting it at our Social Impact page.

ACADEMIC HISTORY OF "CHALKY TEETH"

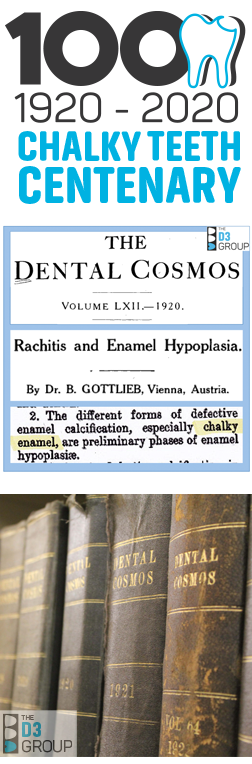

"Chalky teeth" have significant history in the international academic literature, making D3G's translational use of this term all the more justified. Notably, "chalky" was used previously to describe three major D3s and the earliest stage of tooth decay (enamel caries) in erupted teeth, and unhardened enamel in developing teeth, as follows.

Erupted Teeth

One hundred years ago (1920), eminent medical scientist Bernhard Gottlieb described 'chalky enamel' and 'chalky spots' that 'crumble' easily in teeth disrupted developmentally by childhood disorders including "rachitis" (rickets or vitamin D deficiency). In so doing, he raised pivotal questions about the origins of chalky spots (e.g. why are they scattered among normal enamel, and do they reflect cellular or extracellular disruption?) that persist today with Molar Hypomin. In a different context, he later (1944) listed chalky enamel as a feature of early decay attributable to acid attack.

In the 1930s, milder forms of so-called "mottled enamel" (associated with dental fluorosis) were described as chalky enamel (1930, 1932).

In 1945 when hereditary enamel defects (AI) were classified for the first time, malformed enamel was described by American researchers (one a student of Gottlieb) as being chalky – both in terms of appearance ("chalky white" or yellow or brown) and abnormal hardness ("consistency of chalk"). It was further recognised that enamel may appear chalky in other types of developmental defect. In 1949, the original description of "discrete developmental opacities" referred to areas of soft enamel as being "chalk-like". An accompanying photograph showed front teeth with distinct white spots that equate to the "demarcated opacities" we associate with Chalky Molars (and other teeth) today. Soon after (1952, 1954,1955), porous enamel defects (probably opacities and/or early decay) were described as "chalky spots" or "chalky white enamel" and "chalky enamel" was analysed biochemically. A year later, while categorising various types of AI, enamel was described as chalky if somewhat softer than normal, or

cheesy if much softer – given the author came from England, it appears

the phrase "like chalk and cheese" was being referenced.

Roll on to 1986 and enamel was described as chalky white by New Zealand's inimitable Grace Suckling studying severe dental fluorosis.

This description was also applied to early decay (so-called "white

spot lesions") by others three years later. In 1995 and 2001, "chalk

and cheese" resurfaced in the Netherlands with hypomineralised enamel

being described as soft and porous like discoloured chalk or old Dutch

cheese – leading to the term "cheese molars" for what today we call

chalky 6-year molars or Molar Hypomin. At the turn of the century,

cheesy 6-year molars were reborn as Molar-Incisor Hypomineralisation

("MIH"), and demarcated opacities were later categorised as being

"white/chalky", yellow or brown (in order of increasing softness or

crumbliness; see our "chalky picture" near the top of this page).

Soon after, chalky enamel (a modified calcium phosphate) was reported

to have elevated levels of carbonate, making it more like chalk

(calcium carbonate) and hence less resistant to acid.

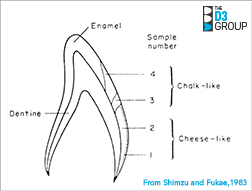

Developing teeth

Whereas the foregoing section covered enamel abnormalities visible in the mouth, immature teeth developing normally inside the jaw are also said to have chalky enamel. Confusingly, in such unerupted teeth, chalky enamel is a normal thing at certain times – being intermediary between soft and hard enamel. And as originally described for AI (1956, see above), "cheesy" has been used to describe developing enamel that's softer – and in this case younger – than chalky enamel. The accompanying illustration of how normal development progresses from cheese-like through chalk-like to fully hardened enamel comes from a 1983 article by Japanese researchers.

Science Translation

In 2013, D3G introduced its Chalky Teeth Campaign hoping that a simplified "chalky teeth terminology" would help laypeople navigate the scientific and clinical complexities of D3s. Following widespread acceptance of "chalky teeth" by the public and healthcare professionals alike, allied terms (chalky enamel, chalky spots, chalky molars) were introduced via mass media avenues (Chalky Teeth Campaign and D3G websites, children's storybook, We Fight Chalky Teeth and Speak 'Chalky Teeth' initiatives). Finally, having gained public and professional mandates, D3G's chalky teeth terminology was "reverse translated" into

academia with a series of high-profile

publications commencing in 2017.

SOCIAL HISTORY OF "CHALKY TEETH"

It's clear the term "chalky teeth" spilled over into society from the dental profession and academia many decades ago – at least "down under" in Australasia. A New Zealand interview-based study reported in 2010 that the diagnosis of "chalky teeth" was a major reason for Kiwis having all their teeth extracted at relatively young ages in the 1940s and 50s – a common understanding being that chalky enamel would "inevitably succumb to dental caries and breakdown". The transcripts (kindly provided by the authors) revealed that one savvy respondent noted his siblings didn't have this problem and attributed the "chalky teeth" diagnosis to a dental school professor in 1948. The investigators concluded "chalky teeth" was used by dental professionals to describe developmentally malformed enamel that was "prone to decay and crumble". Moreover, this tenet was traced back to internationally influential publications by New Zealand dental pioneer Henry Percy Pickerill who contended in the 1920s that "the key to understanding an individual's susceptibility to dental caries was faulty enamel". Similarly in a 1971 Australian study, interviews of "toothless sexagenarians" born in the early 1900s revealed that "8% blamed the loss of their own teeth on the fact that they were 'chalky' or soft and so not restorable". Notably, "chalky teeth" were categorised by the investigator as being distinct from dental caries. The parallels between "chalky teeth of old" (per these two studies, which only came to our attention in 2019) and D3G's adoption in 2013 of "chalky teeth" as a translational tool are quite remarkable – and further evidence that this is a worthwhile path to follow.

A tangential but perhaps much-broader societal connotation for "chalky teeth" came from a series of toothpaste advertisements shown in Australia and New Zealand during the 1970s and 80s (e.g. here and here). A simple "stick of chalk" analogy was used to educate about the enamel-hardening properties of topical fluoride. This led to the schoolteacher ("Mrs Marsh") becoming a pop culture icon, whose educational legacy continues today.

And extending this translational terminology to the USA, "chalky teeth" was used by paediatric dental experts in Seattle, WA to describe Molar Hypomineralisation in a 2011 parenting magazine article. Notably, the term was linked to increased risk of toothache and decay (in both "baby" and "adult" teeth) and consequent need for early intervention – as elaborated in our Chalky Teeth Campaign today. Similarly, in the 1970s, a local dentist in Binghamton, NY described some of his patients as having "chalky teeth" – as recounted by one such patient who told us this means "weak enamel that is conducive to lots of cavities".

On a quite different matter, some writers have recently co-opted "chalky teeth" to describe the "gritty teeth" sensation felt sometimes after eating spinach and other oxalate-rich foods (here, here).

"CHALKY TEETH" AROUND THE WORLD

Given that "chalky teeth" has long proven to be a useful analogy for communicating the clinical and scientific complexities of D3s, how might this term work in languages other than English? As the history

Given that "chalky teeth" has long proven to be a useful analogy for communicating the clinical and scientific complexities of D3s, how might this term work in languages other than English? As the history

of chalk extends right back to the time of cave drawings, it's unsurprising that many "tongues" have a word for "chalk" (nouns are given for 84 languages here). Equivalents for "chalky" are less common however (68 adjectives given here), making it sometimes necessary to say "chalk teeth" or "teeth of chalk" (e.g. dientes de tiza in Spanish).

Please help us expand the following list of "chalky teeth" being used in languages other than English (contact the Secretary).

| Language | "Chalky teeth" equivalent | Literal translation | Examples |

| French | dents crayeuse | chalky teeth | dents crayeuse |

| German | kreidezahne | chalky teeth | kreidezahne |

| Spanish | dientes de tiza | teeth of chalk | dientes de tiza |

| Italian | denti gessosi denti de gesso |

chalky teeth teeth of chalk |

denti gessosi denti de gesso |

| Portuguese | dents de giz | teeth of chalk | dent de giz |

| Catalan | dents de guix | teeth of chalk | dents de guix |

| Greek | κιμωλιακά δόντια | chalky teeth | κιμωλιακά δόντια |

| Turkish | tebeşir dişleri | chalk teeth | tebeşir dişleri |

| Norwegian | krittenner | chalk teeth | krittenner |

| Malay | geraham putih kapur | chalky white molars | geraham putih kapur |