HEALTH RISKS OF MOLAR HYPOMINERALISATION

The hallmark of Molar Hypomineralisation is discoloured enamel that's often soft and porous. Unsurprisingly then, a most serious aspect is the lifelong risk for tooth decay – which, in the case of hypomineralised enamel, may involve a mix of dental caries, acid erosion and enamel breakdown. Consequently, without dental intervention, decay is an almost inevitable consequence in moderate and severe cases of Molar Hypomineralisation (see Grading). Decay may in turn lead to major disruption or even loss of affected molars, often necessitating input from dental specialists where available and affordable (e.g. paediatric dentist, orthodontist, prosthodontist, endodontist, oral surgeon, anaesthetist). On its own, Molar Hypomineralisation often causes sufficient dental pain (toothache) to interfere with eating, drinking and oral hygiene – the latter aggravating risk of decay. Cosmetic issues can also arise, particularly when the front teeth are affected too (Molar Hypomin). As with dental caries, these lifelong issues

can lead to quality-of-life problems including dental anxiety, behavioural

lapses and absences from school or work (learn more).

The specific risks and liabilities associated with Molar Hypomineralisation

have been addressed in numerous studies and can be considered under 5 topic headings as follow:

"UNPREVENTABLE" TOOTH DECAY

Although the terms "tooth decay" and "dental caries" are often used interchangeably in public and professional settings, this is inaccurate for Molar Hypomineralisation (MH). It's well known that a hypomineralised tooth can degrade as a result of mechanical breakdown – typically due to chewing and toothbrushing – and acid attack. Acid attack has two main components – bacterial acids from dental plaque, and "erosion" from dietary acids, reflux or vomiting. We use "caries" in its modern terminological sense, being the breakdown of tooth tissue by bacterial acids. Distinctly however, we adopt the historical meaning of "decay" to cover all components of tooth degradation recognised today (mechanical breakdown, caries, erosion).

Multiple lines of evidence point to MH as a principal risk factor for childhood tooth decay, at both individual and population levels – albeit the findings remain largely circumstantial and unquantified (see below). However, two Australian population studies together provide emphatic evidence that MH accounts for a major proportion of childhood decay. Notably, substantial decay persisted under ideal homecare conditions (good oral hygiene, sugar control, optimal fluoride exposure), presumably because it was underpinned by chalky enamel/MH. It's important to consider such "unpreventable" tooth decay in public health messaging and when talking to families. Unfortunately today's globalised public health message – "tooth decay is preventable" – is only partially true.

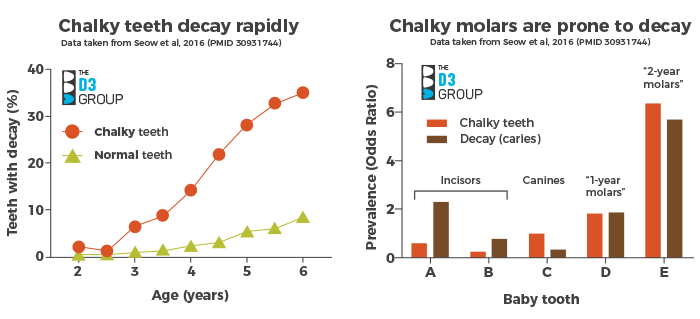

The first Australian study (Seow et al., 2016) established that chalky "baby teeth" (primary dentition) decayed rapidly compared with normal teeth from within the same mouths (i.e. at individual level). To illustrate their findings more clearly, we made two colour-coded graphs (above) from the authors' tabulated data. The left graph shows that chalky teeth decayed much faster than normal teeth, particularly soon after their eruption into the mouth. For example, at age 4 years, chalky teeth had decayed 6-times more often than normal teeth. On the right we see that decay occurred on the 2-year molars mostly, as did chalky enamel (53% and 64% of respective totals). The same pattern was seen for 1-year molars but not the front teeth (incisors, canines). We infer that rapidly-decaying, chalky molars potentially accounted for half of the decay in these preschoolers. This study was particularly strong not only because it tracked the same kids over time (longitudinal study), but also because a rigorous "caries prevention" program (dietary & oral hygiene advice, regular checkups & fluoride treatment) was maintained throughout – so what we're seeing here is essentially "unpreventable decay" at homecare level in a low-caries population. A 2016 Brazilian study of "adult teeth" (permanent dentition) – also longitudinal – made similar findings with chalky 6-year molars, and a report from Columbia extended the link to chalky 12-year molars.

The second "wow" study from Australia (Ha et al., 2021) actually didn't address MH or chalky teeth. Rather the researchers asked what influence 2 main determinants of dental caries – sugar consumption and fluoridated water exposure (also known as risk factors) – had on adult teeth in 8–14-year-olds at national population level (over 16,000 kids examined!). Again we've used colour-coded graphs (above) to highlight salient findings not featured in the article. While the scientifically-wonderful "dose-response" findings for sugar consumption and fluoride exposure appear quite complicated (left graph), our takeaway conclusion is simple (right graph). That is, when "best-case kids" (less than 2 sugar serves daily, ideal fluoridation) are compared with "worst-case kids" (8+ daily serves of sugar, unfluoridated water), a dramatic halving of tooth decay was observed – totally consistent with what's known about caries prevention, as the authors discussed. However, what amazes us is that in these "real life", best-case conditions (low sugar, ideal fluoridation), about 1-in-6 kids (17%) still experienced decay. As this study didn't address MH, cause and effect remain to be established. However, with 6-year molars being the most decayed tooth in this age group (see above & below), it's notable the prevalence of such "unpreventable" decay approximates that of hypomineralised 6-year molars (19% average in Australia, 15% worldwide). Finally, the authors also reported similar findings for baby teeth in 5–10-year-olds, consistent with Seow's 2016 study above.

Combining these two benchmark studies, it seems reasonable to recognise MH as a third major determinant of childhood tooth decay alongside excessive sugar consumption and suboptimal fluoride exposure. The collective findings suggest that (1) chalky molars/MH are largely responsible for "unpreventable" decay in both dentitions, and (2) MH underpinned a major proportion of childhood tooth decay in the studied Australian settings. Clearly, MH-targeted research is warranted to prove the point and address generalisability, realising that variance in MH prevalence and severity will impact the degree of "unpreventability" at population level.

The link between MH and childhood decay isn't new. A groundbreaking 1949 report from the USA linked "chalky spots" (now called "demarcated opacities") to decay, noting firstly in the laboratory that acid corroded the chalky enamel more rapidly than normal enamel. Secondly, in the clinic, linkage was observed between those teeth most frequently exhibiting chalky opacities (the 6-year molars) and the tooth-type already established as most prone to decay (6-year molars, again).

Between these old and new findings resides a wealth of supporting evidence coming from the D3 and caries research fields. However, much of it is circumstantial if not muddled because most studies weren't specifically designed to ask what today we recognise are the key questions, as follow:

- Q1: Is chalky enamel more prone to decay than normal enamel? – yes, it's less resistant to acid attack (being porous and more chalk-like than normal), and also prone to wear away or crumble (during chewing or cleaning), being weaker than normal. Dental plaque also gets extra shelter (hiding places) from the rough/porous surface of chalky opacities, and the sensitivity of chalky enamel (see toothache, below) can hamper plaque removal (tooth brushing).

- Q2: Are hypomineralised teeth more prone to decay than normal teeth in the same mouth? – yes, as seen in the first Australian study above (Study 1, left graph) and reported by others (e.g. here, here).

- Q3: Are 2-year, 6-year and 12-year molars more prone to chalky opacities than other teeth? – yes, as noted above (Study 1, right graph, and 1949 study) and also evidenced by numerous prevalence studies conducted around the world.

- Q4: Are 2-year, 6-year and 12-year molars the most decay-prone teeth in the baby and adult (primary and permanent) dentitions, respectively? – yes, as seen above (Study 1, right graph) and also evident from numerous caries investigations (e.g. here, here, here).

- Q5: Do the commonest locations of decay and D3s on chalky molars coincide? – yes, both hypomineralisation and decay are predominantly located in the "top" (occlusal, or chewing) area of the tooth (e.g. here, here, here and here). Other D3s (surface pits and grooves and 'occlusal fissures') may also contribute but the association with hypomin remains when they're excluded (e.g. here).

- Q6: Are kids with severely hypomineralised molars more prone to decay than mild cases? – yes, as reported for example in Australia and New Zealand.

It follows from this scientific appraisal that (1) childhood decay isn't "preventable" (or even mostly so) as often stated in the healthcare sector, and consequently (2) childhood decay won't "go away" until Molar Hypomin becomes preventable. Fortunately, even partial alleviation would be useful given decay risk lies with severe cases mostly (cf. Q6).

Looking to overcome widespread ignorance around this topic (particularly among dental practitioners and policymakers), it's pleasing that recent literature has not only documented patchy awareness of MH, but also revealed substantial appetite for learning. Other evidence also suggests that D3s increasingly are being prioritised by the "early childhood caries" and broader dental communities (e.g. here, here, here).

Some more reading from around the globe

- In a Dutch study of children with a low overall level of decay, those with hypomineralised 2-year molars exhibited a 3-fold higher experience of dental caries than those without Molar Hypomin (read more)

- In Syria, risk of decay was 7-fold higher in children with hypomineralised 2-year molars (read more)

- In Australia, children with hypomineralised 6-year molars were found to be at 14-fold increased risk of decay (i.e. DMFT) when compared to those lacking this developmental defect (read more)

- Concordantly, a Mexican DMFT study showed that 6-year molars accounted for 89% of total caries in adult teeth of 12–15 year-olds (read more)

- In New Zealand, children exhibited over 11-fold increased risk of decay if their 6-year molars were severely hypomineralised whereas mild/moderate cases had 3-fold higher risk when compared to those without Molar Hypomin (read more).

- A study in Thailand found that children with hypomineralised 6-year molars had 10-fold higher risk for decay on average, with even higher risk (18 fold) for those in the upper jaw (read more).

- In Finland, hypomineralisation was found to be the highest risk indicator for decay in 6-year molars, accounting for a nearly 7-fold higher risk (read more).

- A Brazilian study investigated what happens to hypomineralised 6-year molars that had been graded as mild (i.e. intact opacities, not requiring treatment) at 8-years of age. They found that although only 7% of intact opacities broke down over the following 12 months, this added over 7-fold risk of decay compared to teeth lacking opacities (read more).

- A follow-up study of German adolescents experiencing exceptionally low levels of decay found that, contrary to an earlier report, hypomineralised 6-year molars did carry a significantly higher risk for dental caries. The relatively small added risk in this well-educated, high socioeconomic population is encouraging from a prevention perspective (read more)

TOOTHACHE (DENTAL PAIN)

- In Melbourne Australia, about 20% of children with hypomineralised 6-year molars reported having significant dental pain associated with this condition (read more)

- A Brazilian study found that, among children with hypomineralised 6-year molars, about 35% were sensitive to a blast of air or scratching with a dental probe. Importantly, pain was registered not just in moderate and severe cases, but also kids with (visually) mild hypomineralisation. (read more)

DENTAL TREATMENT NEEDS

- In a Greek study, children with hypomineralised 6-year molars had 11 times the chance of requiring dental restorations when compared to a control group (read more)

- A Swedish study found that, by the age of 9, children with Molar Hypomineralisation had undergone nearly 10 times more treatment on their 6-year molars when compared to healthy controls. Moreover, on average, every defective tooth had been treated twice,

prompting dental anxiety in many children. A follow-up study

showed the need for extra dentistry persisted 9 years later but dental

anxiety had returned to normal levels (read more here and here) - Another Swedish study of 18-year-olds with hypomineralised 6-year

molars found dental restorations had lasted only 5 years on average,

thereby necessitating ongoing treatment. However most cases treated

by extractions had satisfactory outcomes (read more)

ORTHODONTIC NEEDS

- A Danish study found that early extraction of 2-year molars was a major contributor to subsequent orthodontic problems (e.g. crossbite, deep bite) in the adult dentition (read more)

- An English study found that, by the age of 12, hypomineralised 6-year molars had led to a 10-fold higher rate of extraction for these orthodontically important teeth (read more)

- Another study from England reported that hypomineralisation was the second-most-common reason for extraction of 6-year molars. Hence Molar Hypomineralisation underpinned numerous general anaesthetics and often created orthodontic issues (read more)

- In Sweden, a study investigating spontaneous closure of the gap created by extraction of hypomineralised 6-year molars found that nearly half of the children required future orthodontic treatment. About half of this group (20% of total sample) required

orthodontic treatment specifically related to their molar extractions

(read more) - The timing of extraction of hypomineralised 6-year molars affects

the future need for orthodontics, with one study finding that

extractions at the age of 8 to 10 years of age provided the best

orthodontic results (read more)

PSYCHOSOCIAL ISSUES

- A Brazilian study showed that many schoolchildren who had undergone premature extraction of their "baby" molars (i.e. a common fate for Hypomin 2-year molars) experienced a decreased quality of life relating to oral symptoms, functional limitations and emotional well-being (read more).

- An English study found that children with pyschosocial issues surrounding their hypomineralised adult front teeth experienced much-improved quality of life after appearance was improved by cosmetic dental treatment (as pictured, read more)

- It was found that many Columbian schoolchildren with Molar Hypomineralisation experienced negative impacts on their quality of life (read more)

- In Nigeria, schoolchildren with Molar Hypomineralisation often had concerns about their appearance which, together with other related issues, could impact their quality of life negatively (read more)